Before juicy, seasonal tomatoes hit farmers’ markets and backyard gardens, most people reach for the year-round grocery store lineup. Vine-ripes, grapes, cherries, Romas, medley packs, “snacking” varieties – we expect perfect tomatoes any time of year, and the system delivers. (I’ll admit it: Sugar Bombs by Mastronardi Produce are genuinely great.)

But what most shoppers don’t realize (and why would they?) is that beneath that seamless supply lies a decades-long trade war – one that’s now reaching a boiling point. It’s all anyone’s talking about in my corner of the fresh produce world, so I wanted to share some background – and why I think it reveals something bigger about what we value in our food system.

Though tomatoes are naturally seasonal and quick to spoil, they now line US grocery shelves year-round. That seamless abundance didn’t just happen – it was built over decades of breeding breakthroughs, greenhouse innovation, and a supply chain stretching from Canada all the way down to Mexico. With its sunny winters and smart investments in agriculture, Mexico became the undisputed leader in off-season tomato production. The result? Vine-ripened tomatoes available in months that once felt impossible.

(And I mean real R&D – scientists even mapped the genetics of tomato flavor. I remember when that study came out, it was huge news.)

Back then, the US tomato supply followed a predictable rhythm: California dominated the summer and fall, while Florida supplied most fresh tomatoes during winter and spring. Mexico wasn’t yet the winter tomato powerhouse it is today.

For decades, these tomatoes weren’t bred for flavor – they were bred to survive the journey. Picked green, gassed with ethylene to turn red, and shipped long distances, they ended up as the pale, mealy slices many of us remember from ’90s fast food burgers. I grew up with two sisters who detested tomatoes – and I blame those flavorless discs. (They’re “working on it” now, as if it’s a personal challenge to overcome.)

But the problem wasn’t picky eaters – it was the system. In 1996, biotech introduced the Flavr Savr tomato (the name!), engineered to delay ripening and improve shelf life. But it never took off, and flavor still fell short. Retailers and fast food chains stuck with firm, sturdy varieties that could handle industrial processing and slicing.

Then, starting in the late ’90s, shoppers began encountering – and really enjoying – better-tasting imports from Mexico. This shift was fueled by growers adopting protected agriculture and greenhouse technology, plus milder winters that made fresh, vine-ripened tomatoes available during off-season months.

When I worked at Red Tomato in 2011, we championed this flavor-first agenda. Our name was a nod to rebellion: the idea that tomatoes could be red, ripe, local – and actually delicious. Partnering with researchers, I learned tomatoes could even taste umami. We brought Northeastern heirlooms to Trader Joe’s, which was a crash course in just how hard it is to prioritize flavor in a system designed for uniformity and efficiency.

Of course, the ’90s also brought major shifts that reshaped the industry: NAFTA, a sharp peso devaluation, and massive investment in Mexican agriculture. Growers transformed open fields into greenhouses and shade houses, borrowing innovations from Spain, Israel, and the Netherlands. These advances meant better yields, less chemical use, and more resilience against climate challenges. With strong US importer partnerships, Mexico quickly became the winter tomato juggernaut.

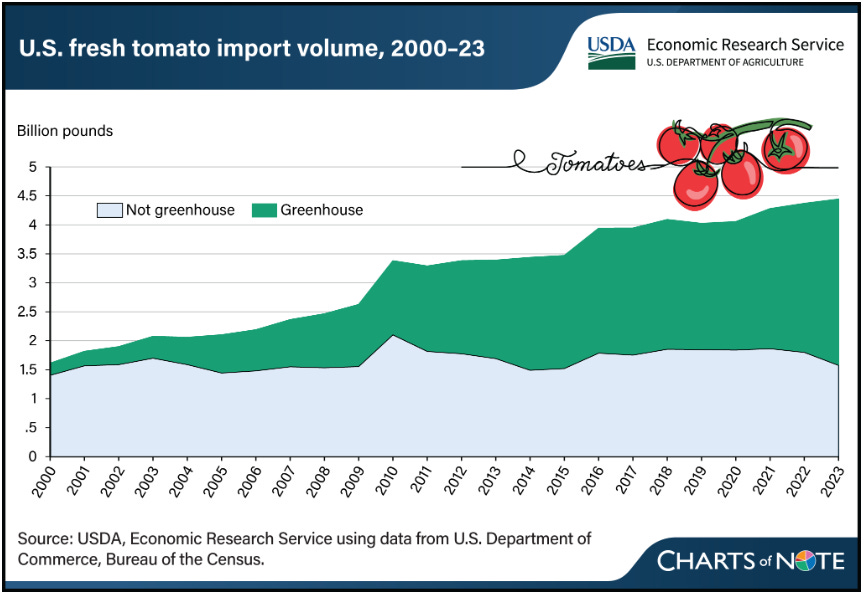

Today, nearly 70% of fresh tomatoes eaten in the US are imported – about 90% of them from Mexico. In 2024 alone, the US imported $3.34 billion worth of Mexican-grown fresh tomatoes, accounting for the vast majority of total imports.

The scale is staggering.

Much of that trade moves through border hubs in Arizona, Texas, and California – including the one where I grew up. My family’s produce business was deeply involved in cross-border trade, though never in tomatoes. Still, we’ve always felt the ripple effects of shifts in the industry.

With growth came tension. US growers, especially in Florida, watched their dominance slip. Florida’s tomato industry had long relied on a handful of varieties bred for shelf life and uniformity. Facing recurring challenges – disease, hurricanes, and mounting competition – innovation became nearly impossible.

Labor concerns added fuel to the fire. Though egregious abuses are thankfully rare, labor issues persist across agriculture worldwide. Both sides have been scrutinized: the LA Times has documented harsh conditions on some Mexican tomato farms, while the book Tomatoland exposed systemic exploitation in Florida’s Immokalee region.

To complicate matters, many US companies that import Mexican tomatoes also operate farms or partner with growers there. The result is a tangled web – part rivalry, part symbiosis – shaped by a food system built for year-round, national distribution.

For years, a suspension agreement between the US Department of Commerce and the Mexican tomato industry helped stabilize prices and prevent dumping by setting minimum import prices. But on Monday, that deal unraveled after the Department of Commerce announced it would terminate the agreement, citing what it described as noncompliance by some Mexican producers – an allegation Mexico denies. Without the agreement in place, Mexican tomato imports will now face a 17% anti-dumping tariff, a trade penalty meant to counteract goods sold below fair market value.

This tomato fight isn’t just about fruit – it’s a proxy war over the future of agriculture: protectionist or collaborative, consolidated or regional, flavor-driven or profit-optimized. The tension is most visible in Florida, where a tomato industry once defined by dominance now depends not on taste or freshness, but on policy battles to stay afloat. Tariffs may buy time, but they don’t address the deeper structural issues – like labor, climate, and the razor-thin margins facing growers on both sides of the border.

Tomatoes aren’t just salad ingredients or burger slices – they’re a window into the complex intersections of trade, labor, and technology on our plates. And yet, when someone bites into a fresh tomato and says, “Wow, that tastes like summer,” it’s a hopeful reminder that good food, and better systems, are still within reach.

Update: As I was working on this piece, President Trump announced yet another round of tariffs on goods from our North American neighbors that would, in theory, would come on top of the anti-dumping tariff. Regardless of the outcome, these policies can send shockwaves through industries that rely on daily, perishable shipments – my dad was even interviewed by NPR last time around. I’ll be watching closely and will follow up with updates.

More reading:

The Tomato Tariff Racket (WSJ)

Industry groups warn tomato trade shift could raise prices, strain supply chain (The Packer)

Effects of trade and agricultural policies on the structure of the U.S. tomato industry (Food Policy, 2017)

Bean There, Still Cooking is free while I find my rhythm. If any of this resonates – or if you want to see this newsletter grow – consider sharing it with a friend.

Sister here-- while I will continue to remove pink, soggy, out of season slices on my burgers probably forever, I am happy to report that I now fully take advantage beautiful seasonal tomatoes raw, cooked, salted, vinegary, whole, in sauce form, etc. etc. etc.

Thank you for this great recap of tomatoes, innovation, and all the complexities that exist behind the food we eat. This is a fantastic analysis of the issue.